It is likely that Liszt derived the idea of thematic transformation as a unifying process from Schubert’s Wanderer Fantasy, a work which he himself transcribed for piano and orchestra in 1851. Schubert’s themes run through all four movements of the fantasy in varied forms The four movements are played without a break, and outline a symmetrical key scheme— C, E, A flat, C. This kind of formal plan held a strong attraction for Liszt, and many of the works of his Weimar period follow this model, besides the Piano Sonata in B Minor also the first piano concerto is another example.

The sonata was published in the spring of 1854 and dedicated to Robert Schumann. Liszt meant this as a reciprocal gesture to Schumann in response to his being the dedicatee of the latter’s Fantasy in C major (1839), a work that Liszt described as sublime. However, Schumann never knew of the B Minor Sonata’s existence since by the time a copy of the newly published work arrived at the Schumann’s home in May, 1854, Schumann was already at the asylum at Endenich.

Clara Schumann could have included the work in her repertory, if she had been so inclined, but she chose not to do so. In her diary she described the sonata as “a blind noise … and yet I must thank him for it. … It really is too awful.” (Litzmann, Berthold, 1902-08)

Unfortunately, Clara’s opinion was not atypical. During this period, and especially in this part of Germany, Liszt was often treated to an unkind dismissal by the musical society. When the work received its première performance, in Berlin, on January 22, 1857, nearly four years after its composition, it provoked a minor scandal among the conservative critics, from which it recovered with difficulty. Rarely did such great music get off to a less promising start. (Walker, 1983)

Liszt always felt that the new music he and his group (Chopin, Berlioz, Wagner) were writing needed new forms for expression. He did not see the sense in merely pouring their “new pudding” into an old form. Consequently he created new forms which would allow him greater flexibility while still maintaining unity (and echoing the old sonata form in basic structure). This he did with the Sonata, the Concerto in E flat and the Faust Symphony.

The principle which he established was an important one for future generations; the serial technique of Schoenberg, for instance, uses precisely the methods of Liszt’s thematic transformation within the framework of an entirely different language, and it is even possible that future twelve-note composers will turn to forms resembling Liszt’s rather than those of the classical composers in the search for a type of framework to correspond to their new methods of expression. In any case Liszt’s Sonata remains a landmark in the history of nineteenth-century music, not only as a highly successful application of new technical methods, but as a fine, moving and dramatic work in itself. (Buechner and Searle, 2013)

No other work of Liszt has attracted anything like the same amount of scholarly attention as the B-minor Sonata. The number of divergent theories it has provoked from those of its admirers who feel constrained to search forbidden meanings are many.

- The sonata is a musical portrait of the Faust legend , with “Faust,” “Gretchen,” and “Mephistopheles” themes symbolizing the main characters. (Ott, 1981)

- The sonata is autobiographical; its musical contrasts spring from the conflicts within Liszt’s own personality. (Raabe, 1931)

- The sonata is about the divine and the diabolical; it is based on the Bible and on Milton’s Paradise Lost. (Szász, 1984)

- The sonata is an allegory set in the Garden of Eden; it deals with the Fall of Man and contains “God,” “Lucifer,” “Serpent,” “Adam,” and “Eve” themes. (Merrick, 1987)

- The sonata has no programmatic allusions; it is a piece of “expressive form” with no meaning beyond itself— a meaning that probably runs all the deeper because of that fact. (Winklhofer, 1980)

Liszt was generally silent about this work and offered no words of any kind on the question of its program – or lack of it. (Walker, 1983)

The sonata unfolds in approximately 30 minutes of unbroken music. While its four distinct movements are rolled into one, the entire work is encompassed within the traditional Classical sonata scheme— exposition, development, and recapitulation. Liszt has effectively composed a sonata within a sonata, which is part of the work’s uniqueness.

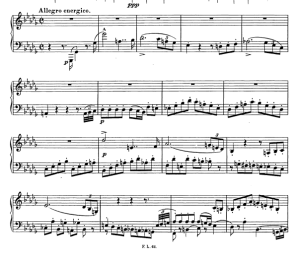

Liszt was very economical with his thematic material, indeed, the very first page contains the three motivic ideas that provide the content, transformed throughout, for nearly all that follows.

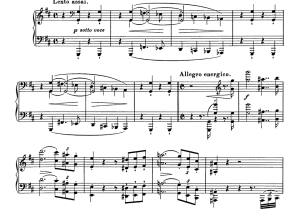

The first theme is a descending scale marked sotto voce, full of ominous undertow it is destined to reappear at crucial points in the work’s structure. Leading immediately to a jagged, forceful theme in octaves.

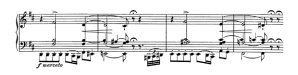

This is quickly followed by a hammering marcato idea in the left hand.

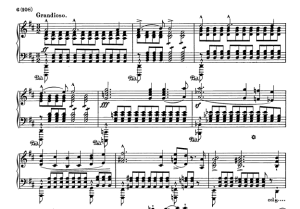

A dialogue ensues, with mounting energy, until reaching the noble grandiose second subject in D major.

Liszt transforms the left-hand theme into a lyrical melody of exquisite loveliness.

The slow movement, an Andante sostenuto of haunting beauty, is the centerpiece of the sonata.

This fully fledged “compound ternary” form features in quick succession a number of themes heard earlier in the sonata in a tour de force of thematic economy.

The final recapitulatory section is launched by a driving fugato of contrapuntal skill which leads to the compressed return of the opening material. Calling upon every intellectual resource and fully exploiting the pianist’s technical arsenal, it is at this point where a performer’s concentration might flag. But this final section has only just begun, and a pianist needs to have reserved fuel in his tank if he is to turn in a successful performance of the sonata.

Very few works of the nineteenth century attempted to telescope fugues into sonatas, and with the exception of Beethoven’s, none does it more successfully. The major difficulty is that the number of places within a sonata structure where one can actually introduce a fugue without harming both forms is strictly limited; one stands a better chance of mixing oil and water. With unerring insight, Liszt has his fugato function as a development section, in which capacity it also serves as a lead-back to the recapitulation. At one point the fugato subject is turned upside down and presented in counterpoint against itself: Liszt continues to ring the changes on his basic material throughout the sonata. (Buechner and Searle, 2013)

Liszt builds the music to one last titanic climax until finally a dramatic silence ushers in the twilit epilogue: the andante sostenuto melody reappears to serene and touching effect and the curtain comes down on this compositional tour de force.

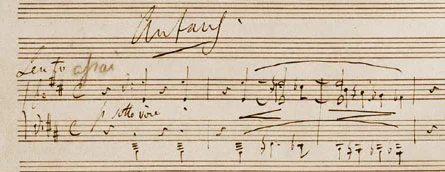

Liszt originally intended the sonata to end with a loud flourish; the manuscript reveals that the inspired quiet ending with which the work now concludes came to him as an afterthought. Posterity must be grateful for the unpredictable ways of genius. After a cataclysmic climax, followed by a long silence, Liszt brings back the soft Andante sostenuto, which seems to cast a benediction over all that has gone before, and the sonata expires with the same descending scale with which it began.

Sources:

- Buechner, Sara D, and Humphrey Searle. The Music of Liszt. 2013. eBook.

- Hamilton, Kenneth, “Liszt’s early and Weimar piano works,” in The Cambridge Companion to Liszt, ed. Kenneth Hamiton, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2005.

- Litzmann, Berthold. Clara Schumann: Ein Künstlerleben. 3 vols. Leipzig, 1902– 08.

- Lucie Renaud, Lucie, translated by Peter Christensen, Notes for the Analekta album Années de pèlerinage – Suisse (Years of Pilgrimage – Switzerland), André Laplante, https://www.analekta.com/en/album/Liszt-Annees-De-Pelerinage-Suisse.591.html, accessed Sept. 8, 2010

- Merrick, Paul. Revolution and Religion in the Music of Liszt. London, 1987.

- Ott, Bertrand. “An Interpretation of Liszt’s Sonata in B minor.” Journal of the American Liszt Society (Louisville, Ky.) 10 (December 1981), pp. 30– 38.

- Raabe, Peter. Franz Liszt: Leben und Schaffen. 2 vols. Stuttgart, 1931; rev. ed., 1968.

- Szász, Tibor. “Liszt’s Symbols for the Divine and Diabolical: Their Revelation of a Programme in the B-minor Sonata.” Journal of the American Liszt Society (Louisville, Ky.) 15 (June 1984), pp. 39– 95.

- Walker, Alan, Franz Liszt: Volume 1, The Virtuoso Years: 1811-1847 (New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1983.

- Walker, Alan. “Franz Liszt: The Weimar Years, 1848–1861.” Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1989.

- Winklhofer, Sharon. Liszt’s Sonata in B minor: A Study of Autograph Sources and Documents. Ann Arbor, 1980.

Which of these themes is sometimes referred to as the crucifixion theme? We talked about this piece extensively in my grad piano lit class, but right now I can’t remember.

Excellent post!

The cross motif is a three note motif coming from the fifth, sixth and eighth degrees of the major scale (or so-la-do’ using tonic solfege).

This is a brilliant, helpful analysis!!